Credit: Circa

Credit: CircaIn Conversation with: Ai Weiwei

“My definition of art has always been the same. It is about freedom of expression, a new way of communication. It is never about exhibiting in museums or about hanging it on the wall. Art should live in the heart of the people. Ordinary people should have the same ability to understand art as anybody else. I don’t think art is elite or mysterious. I don’t think anybody can separate art from politics. The intention to separate art from politics is itself a very political intention.„

— Ai Weiwei

Ai Weiwei (b. 1957, Beijing) is one of the most influential artists and provocateurs of our time. He is celebrated for blending Chinese history and tradition with artistic expression and political activism, all within a wholly contemporary practice. Beyond traditional mediums, his artistic work extends to architecture, documentary filmmaking, and large-scale public installations, each serving as a form of human rights activism, cultural commentary, and critiques of the global imbalance of power.

Born into exile due to his father’s political persecution, Ai Weiwei's early life was marked by hardship, shaping his lifelong commitment to questioning authority. This commitment has often made him a political target in the past. He studied at the Beijing Film Academy before moving to New York in the 1980s, where he was influenced by conceptual art and artists such as Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol. Returning to China in the 1990s, Ai Weiwei emerged as a key figure in contemporary Chinese art while also co-founding independent art spaces and experimenting with radical forms of artistic expression. After years of surveillance and restrictions, he was eventually allowed to leave China in 2015 and has since lived in Germany, the United Kingdom, and Portugal.

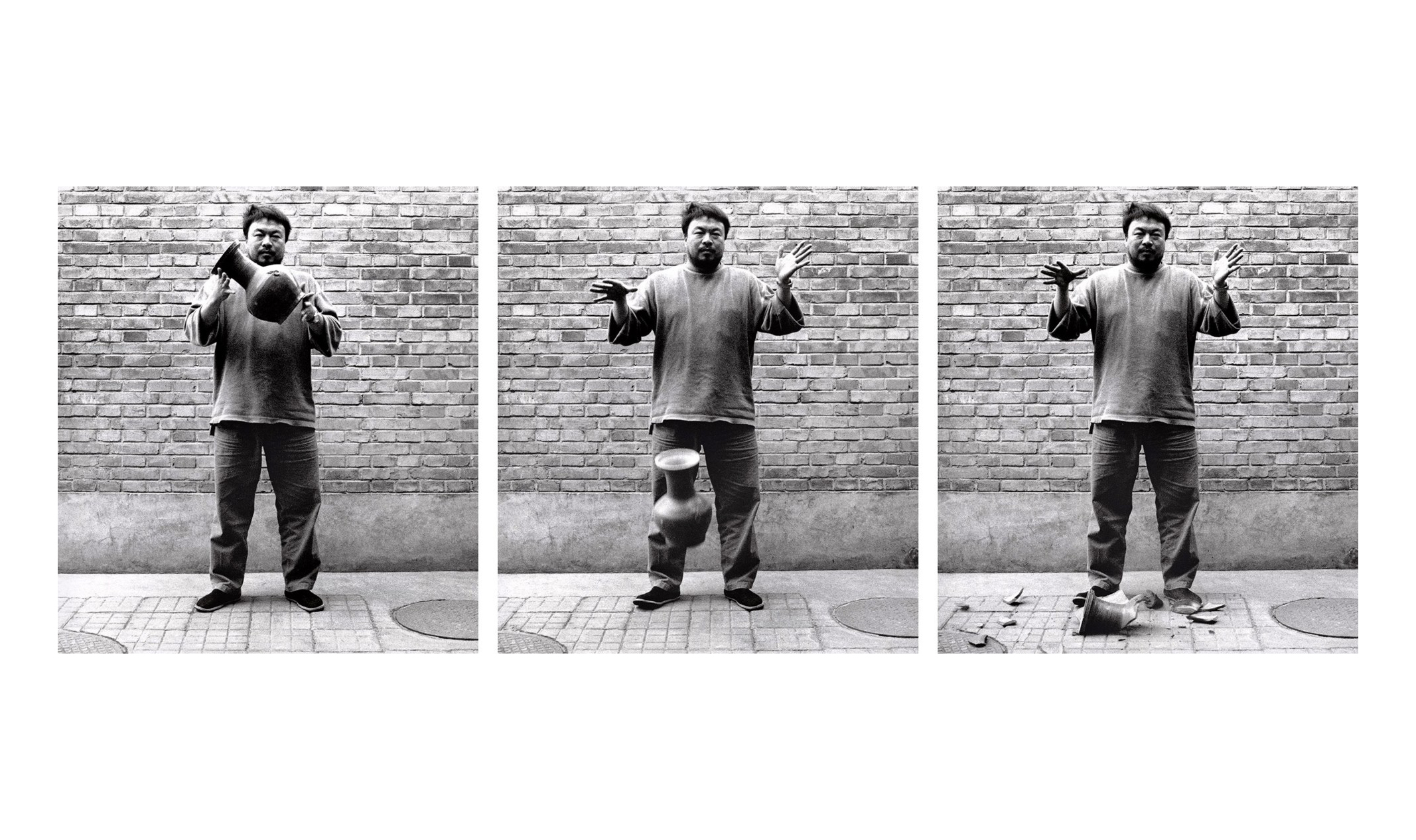

Ai Weiwei gained international recognition through powerful works such as Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (1995), Sunflower Seeds (2010), Neolithic Vase with Coca Cola Logo (Gold) (2015), Illumination (2019), and Straight (2008–2012), a poignant memorial to the victims of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake. Ai Weiwei’s works are held in major museums worldwide and have been exhibited in leading institutions such as Tate Modern, the Royal Academy of Arts, and the Venice Biennale.

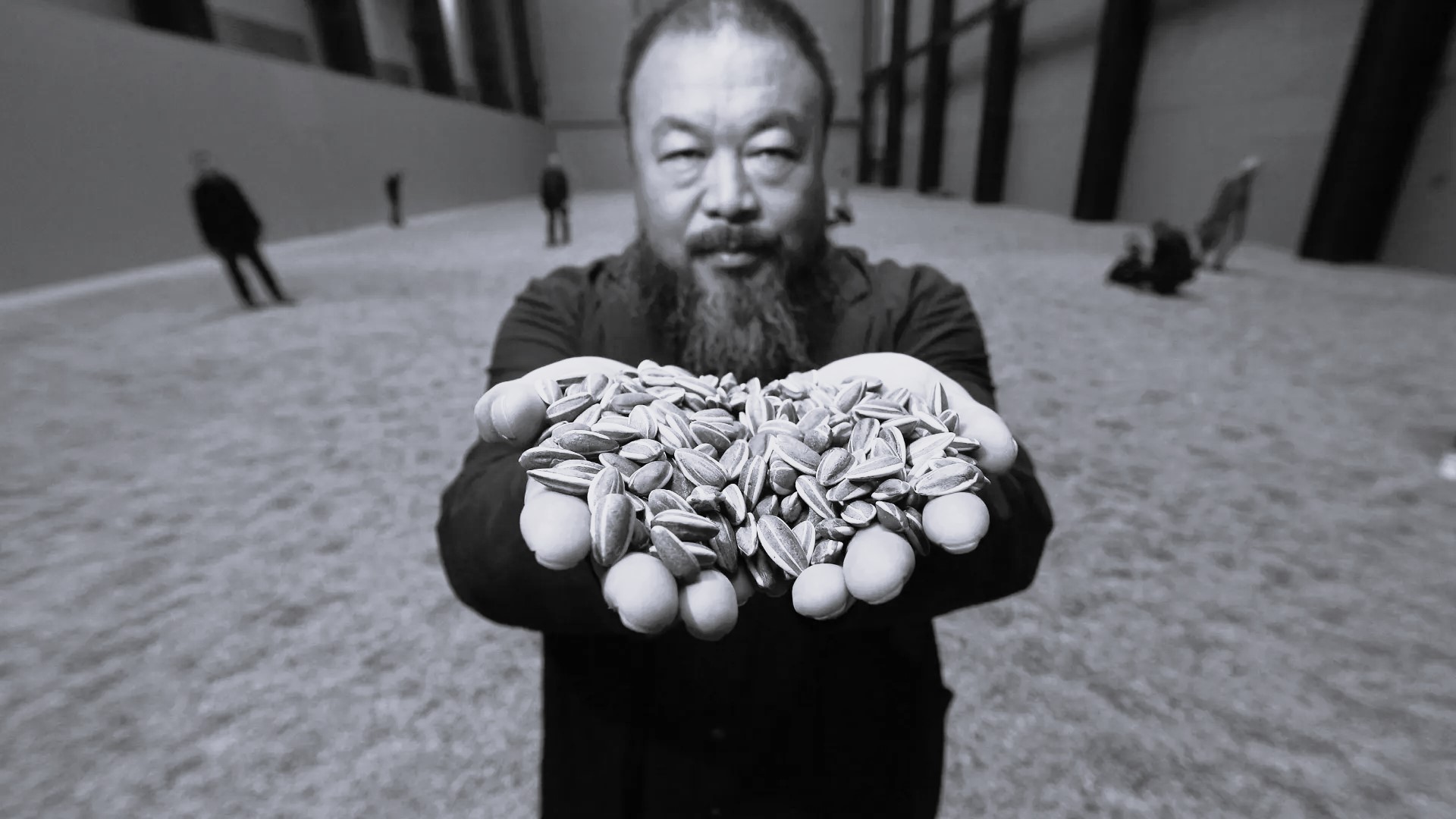

One of his most famous politically motivated works include Sunflower Seeds (2008), exhibited in Tate Modern in 2010 and Straight, which addressed the 2008 Sichuan earthquake by creating art from collapsed schools. His relentless pursuit of truth and justice, coupled with his innovative artistic vision, continues to inspire global audiences and redefine the role of art in society. As Ai Weiwei himself asserts, “Everything is art. Everything is politics.”

Ai Weiwei with ‘Sunflower Seeds’, 2010, Getty Images

Ai Weiwei with ‘Sunflower Seeds’, 2010, Getty Images Courtesy of Thierry Bal

Courtesy of Thierry Bal

In our co-publishing project with Ai Weiwei, we had a chance to sit down with Ai Weiwei and ask him a couple of questions:

Q: I have been told you „don’t like Monet“. What inspired you to create the complex original artwork? Why this subject?

I never said that I ‘don’t like Monet.’ It’s just that I’m not particularly drawn to Impressionism. I took on this theme because my father loved Impressionism. While studying in Paris, he exhibited one of his works in a show under Monet’s name. For me, this piece is more about my father than about Monet himself.

Q: As you never create work for the so-called „beauty“: How does „Les Nuages“ connect with your personal biography? Do your main artistic theme „freedom of speech“ and personal expression manifest in this particular artwork?

What I value most in art is its historical development and its connection to reality. Personal experiences that lack a link to reality hold little interest for me. Monet, for example, painted over 200 paintings of this theme in his final 20 years—a phenomenon I find intriguing, as it mirrors the reiteration seen in many artists’ work. For me, this serves as a readymade to express my personal experiences and reflections on aesthetics. Using personal insights to reinterpret traditional aesthetic discourse is, indeed, an essential exercise of free expression in the realm of art.

Q: You have been working with LEGO bricks for about 10 years now. Why this choice and what added value do they bring to the realisation of your ideas?

I work with toy bricks—though not necessarily LEGO, as they once refused to sell to me. My choice stems from a lifelong aversion to brushwork on surfaces, which I find overly individualistic, tangled with realism, and heavily influenced by personal taste. I've always sought a more detached form of expression, one that stands apart from personal preference. Toy bricks offer a more distanced, objective medium, a choice not unique to me. The ancient Greco-Romans used mosaics to create art, and today, toy bricks resonate with the pixelated digital expressions seen online.

Q: This print echoes digital pixelation – what is your relationship with technology?

Technology merely helps us solve certain problems quickly; it cannot accomplish much beyond that. As a product of rationality, technology, through the output of rational processes, often erases what we consider individual expression. While it can be effective at times, I believe that, more often than not, it has the potential to be destructive.

Q: What is the reason you like to do editions of your original works?

The reason is quite simple. When an artwork is considered a unique original, its quality as being unique elevates its added value. Yet, what matters more to me is the accessibility and reach of expression; with a lower price, art can be made more widely available to the public. I believe that aesthetics should not be monopolized but should participate in a broader, more inclusive conversation.

Ai Weiwei, Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, 1995 (printed 2017), Three gelatin silver prints, 148 x 121 cm each (photo: © Ai Weiwei)

Ai Weiwei, Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, 1995 (printed 2017), Three gelatin silver prints, 148 x 121 cm each (photo: © Ai Weiwei)“The power of my artwork comes not from the act but from the audience's attention, the challenge to their values... People always ask me: how could you drop it? I say it’s a kind of love. At least there is a kind of attention to that piece.„

— Ai Weiwei

Image: Ai Weiwei, Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, 1995 (printed 2017), Three gelatin silver prints, 148 x 121 cm each (photo: © Ai Weiwei)